Welcome to the Pre-Conference Conversations for the New England American Studies Conference. We're writing about the things we'll talk about the conference--join the conversation!

Monday, October 8, 2012

Workshop: "Samson Occom, Early American Archives, and Digital Humanities”

The digital turn has had an enormous effect on our ability to present manuscript documents, which predominate in the early period, as well as the literature, history, and culture of ethnic groups. At the same time, digital technology allows us to explore post-Eurocentric approaches to editing, presenting, annotating, and repatriation of sensitive materials. My current project, the Occom Circle, brings together these three elements of the digital revolution, which I will explore this coming Saturday afternoon in a workshop featuring the project.

The Occom Circle is a digital scholarly edition of works by and about Samson Occom (1723-1792), a member of the Mohegan tribe of east-central Connecticut. Occom was a Christian minister and Indian missionary to various tribes, as well as an educator, pan-tribal leader, and public intellectual, and is considered the first major Native writer in North America. Many of his papers are in the Libraries at Dartmouth College, along with the papers of Eleazar Wheelock, a Congregational minister who was Occom's teacher and mentor and who parlayed his success in shaping Occom as a missionary into a veritable educational industry, establishing, first, an Indian Charity School in Lebanon, CT, which he later moved to the wilds of New Hampshire where it became Dartmouth College. The relationship of these two men is fascinating, and we will explore it through letters they wrote to each other. I will also talk about how digital editions can advance a post-Eurocentric paradigm for multi-ethnic projects (I am also eager to talk with the folks presenting on the Omeka software) and how digital humanities is radically changing how we do and define our work (this touches on Jonathan Silverman's blog post about the roundtable "The Misread Professor".

But the really fun part will be trying our hands at transcribing, reviewing, marking up and validating letters from the the collection. Unfortunately, I cannot bring the originals along but I will have copies and access to pretty good facsimiles, (with a great zoomify applet) like the one below. It's the first page of what I call "the break-up letter" between Occom and Wheelock! (Occom was angry that Wheelock sent him to Europe to collect funds for the Indian Charity School and then absconded to New Hampshire with them but did not enroll many Indians at the College.) But don't worry, I won't assign this letter in the workshop--it's too faded and hard to read, and I have done a fair transcription already that we can examine. If you would like to learn more about digital editing, markup, and TEI headers, and try your hand, please join me

and BRING YOUR LAPTOPS.

See you there.

Ivy

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

Native American Contemporary Song Lyrics: The New Ghost Dance Literature?

Native American oral literature has been commonly

categorized as originating thousands of years ago as some kind of ancient

artifact, which comes down to us from a distant past rather than moments of a

living poetry. In an effort to explore

this myth, I investigate the literature of modern-day Native American song

lyrics taken from the 2011 Native American Music Awards (NAMMYS) winning Pop, Rock,

and Song-Single of the Year songs.

The limitation or exclusion of Native oral literature from

the 21st century American canon is what Jace Weaver calls “a way of

continuing colonialism…and denies to Native literary artists who choose other

media any legitimate or ‘authentic’ Native identity.” Oral poetry, or song lyrics, are another

literary avenue in which Native Americans can express their worldviews and

demonstrate what Gerald Vizenor calls “survivance,” Weaver calls “communitism,”

Robert Warrior calls “intellectual sovereignty,” and Georges Sioui calls

“autohistory.” Although some critics

have described Native Americans as finding themselves in-between two cultures,

the most recent song lyrics indicate they are participating in both cultures.

Selecting a few threads from the mainstream cultural cloth

and pulling them through to the Native cultural fabric (such as the musical

award format, song verse configuration, and elements of Western technology) is

a way for indigenous people to stabilize identity by getting recognition, reinforce

traditional values and customs between generations, and share worldviews.

The Internet is the new campfire.

The result is not only survival of a culture, but the

beginning of vocalizing a resistant, yet positive identity by dispelling the

historical, descriptive inaccuracies using worldviews to illustrate new

perceptions of identity. There is an

ongoing process of negotiating the forces of assimilation into mainstream

American culture, but modern song lyrics are one way Native Americans appear to

regenerate and maintain their foundational culture.

Lindy Hensley

M.A. in English candidate

University of St. Thomas

Sunday, September 16, 2012

Identity Creation, Region and Race in Popular Country Music Lyrics and Tea Party Rhetoric

At this conference, I will present a paper entitled “Backroads and the American South: Identity Creation, Region and Race in Popular Country Music Lyrics and Tea Party Rhetoric.” I will be presenting as part of a panel on “Music, Meaning and Identity.”

My exploration of this topic began in the odd juxtaposition of, on the one hand, long drives spent listening to the few FM radio stations that come in on the lonely, winding roads of rural Maine, and, on the other hand, my work as a graduate student, studying regionalism and the writings of scholars like Lori Robison and Richard Brodhead.

An example:

“The pull of the idea of the country is toward old ways, human ways, natural ways. The pull of the idea of the city is towards progress, modernization, development.” – Raymond Williams

AND

Popular country music, like the song above, which peaked at #15 on the Billboard country charts in September of 2010, pulls the lifestyle and ideology described by Josh Thompson from the margins -- from "way out here" -- to the center of mainstream pop-culture.

In part, this paper – which is hopefully only the beginning of a larger project – is about the repetitive narratives found in country music lyrics. In a broader sense, however, it explores a socio-political climate in the post-9/11 (and even more specifically, post-2008) United States.

In brief, my argument is this: Country music tropes function to create and perpetuate a specific relational identity that celebrates a rural, working-class lifestyle and conservative social values, and opposes modernity, urbanity, wealth and intellectualism. Further, through regional nostalgia, this identity takes on racial overtones. I offer a close-reading of these lyrics and explore their appeal in the contemporary moment. This essay suggests that the identity creation and “othering” that occur in country music resemble the rhetorical strategies used in conservative politics – particularly those used by the Tea Party. In combination, a dialogue is formed that shapes a particular notion of who and what is “American.” Ultimately, I wish to explore the role this pop-cultural form plays in a larger discourse of belonging, power, and enfranchisement.

To listen to/view one of the songs from the sample I use in my paper, see: Toby Keith, “Made in America.”

(This song reached #1 on the Billboard country charts in 2011. It also reached #40 on the Billboard “hot 100” chart.)

-- Liz Swasey

Sunday, September 9, 2012

Mapping Cotton 1862-ish

It’s been a challenge finding time to post during the first week of

classes, and I’m sure this post’s lateness will not detract from its

less-than-greatness.

I’m part of the pecha kucha roundtable on “the Spatial Turn” at least in part because I attended an Arc-GIS course with Ryan Cordell at DHSI in 2011. My goal in that course was to learn enough about Arc-GIS to try out using it to work with documents associated with a set of European itineraries from 1862. Previously, I had worked with a technical liaison from our campus’s Library and Information Services to map some information associated with a woman’s journal from the 1870s. I presented preliminary results from that work at Harvard a few years ago, and I’ll be talking about that project again as part of a series on Digital Humanities for the undergraduate honors program at the University of Kansas in spring 2013.

My interest in mapping the sources of raw cotton in the U.S. South and their destinations for processing in New England in 1840 and 1850 arises from efforts to further contextualize one of those itineraries. My presentation at NEASA will focus on work in progress as I explore effects of the U.S. Civil War on the cotton industry in New England for a paper I will present at a conference sponsored by the Massachusetts Historical Society in spring 2013.

One of the account books among the primary sources we are researching in the Wheaton College Digital History Project documents the operation of a mill that produced cotton batting in Norton, Massachusetts, in the late 1840s. This account book documents the geographical sources of the raw cotton used in the mill, including Apalachicola, Florida, as well as New Orleans. It also refers to the broker from whom the raw cotton was purchased, William J. King of Providence, Rhode Island, who traded on the New York exchange.

The cotton industry shifted in Norton in the 1840s as the wealth of the Wheaton family was transferred from one generation to the next. I am interested in exploring ways in which this microhistorical set of events at the level of family and town might open up questions at the state and national level during a significant period in the economic and political development of the nation.

At the most basic level, mapping of the cotton production has shown correlations with the expansion of slavery for the decades preceding the U.S. Civil War. And last year, Frederick Law Olmstead’s 1861 map of “The Cotton Kingdom” was featured in historian Susan Schulten’s contribution to the “Disunion” blog in the New York Times. Might there be scholarly benefit in examining geospatial information about the sources and destinations of raw and processed cotton at a more granular level?

Kathryn Tomasek

Wheaton College

Norton, Massachusetts

I’m part of the pecha kucha roundtable on “the Spatial Turn” at least in part because I attended an Arc-GIS course with Ryan Cordell at DHSI in 2011. My goal in that course was to learn enough about Arc-GIS to try out using it to work with documents associated with a set of European itineraries from 1862. Previously, I had worked with a technical liaison from our campus’s Library and Information Services to map some information associated with a woman’s journal from the 1870s. I presented preliminary results from that work at Harvard a few years ago, and I’ll be talking about that project again as part of a series on Digital Humanities for the undergraduate honors program at the University of Kansas in spring 2013.

My interest in mapping the sources of raw cotton in the U.S. South and their destinations for processing in New England in 1840 and 1850 arises from efforts to further contextualize one of those itineraries. My presentation at NEASA will focus on work in progress as I explore effects of the U.S. Civil War on the cotton industry in New England for a paper I will present at a conference sponsored by the Massachusetts Historical Society in spring 2013.

One of the account books among the primary sources we are researching in the Wheaton College Digital History Project documents the operation of a mill that produced cotton batting in Norton, Massachusetts, in the late 1840s. This account book documents the geographical sources of the raw cotton used in the mill, including Apalachicola, Florida, as well as New Orleans. It also refers to the broker from whom the raw cotton was purchased, William J. King of Providence, Rhode Island, who traded on the New York exchange.

The cotton industry shifted in Norton in the 1840s as the wealth of the Wheaton family was transferred from one generation to the next. I am interested in exploring ways in which this microhistorical set of events at the level of family and town might open up questions at the state and national level during a significant period in the economic and political development of the nation.

At the most basic level, mapping of the cotton production has shown correlations with the expansion of slavery for the decades preceding the U.S. Civil War. And last year, Frederick Law Olmstead’s 1861 map of “The Cotton Kingdom” was featured in historian Susan Schulten’s contribution to the “Disunion” blog in the New York Times. Might there be scholarly benefit in examining geospatial information about the sources and destinations of raw and processed cotton at a more granular level?

Kathryn Tomasek

Wheaton College

Norton, Massachusetts

Friday, August 31, 2012

Networks of Nineteenth Century Newspapers

Meredith McGill's American Literature and the Culture of Reprinting brought the widespread practice of textual reuse in the antebellum print market to scholarly attention. In her study, however, McGill was forced to focus on three largely canonical authors: Poe, Dickens, and Hawthorne, largely because the physical archive makes discovering unknown histories of reprinting incredibly difficult. If one doesn't already know a particular story or poem was popular and widely reprinted, it's awful hard to start finding those reprints.

Digital archives and text mining perhaps offer a new way into the record that may allow us to discover many more (and many previously unknown) histories of reprinting. Histories of reprinting can also be thought of histories of popularity—and thus are useful windows into the priorities of the period. I've worked with a colleague in computer science to begin automatically uncovering new histories of reprinting in the Library of Congress' Chronicling America collection. The results of this text mining look something like this:

Digital archives and text mining perhaps offer a new way into the record that may allow us to discover many more (and many previously unknown) histories of reprinting. Histories of reprinting can also be thought of histories of popularity—and thus are useful windows into the priorities of the period. I've worked with a colleague in computer science to begin automatically uncovering new histories of reprinting in the Library of Congress' Chronicling America collection. The results of this text mining look something like this:

Each row lists two publications, each's publication date, a link to where each can be found within the archive, and the text they seem to share. After crawling only a fraction of the archive, we've already uncovered hundreds of potential reprinted texts—most of which I've never encountered as a scholar of the period. What can be done to make sense of so much new data?

Network theory perhaps offers a solution. Here's a network graph of all Edgar Allan Poe's fiction in periodicals—again I find myself working with data we as scholars already have on hand. In this graph, the nodes (the circles) represent individual publications. The edges (the lines between the circles) represent shared texts between publications. The edges are thicker based on how many reprints a given pair of publications share. A given node is larger or smaller based on how many other nodes connect to it.

Such a graph offers a large-scale model of how Poe's fiction moved around the county. Close-knit communities of textual sharing cluster together on the graph, and the central publications that shaped Poe's national reputation clearly emerge from the graph.

While it might not shock Poe scholars to see the <i>Broadway Journal</i> or <i>Southern Literary Messenger</i> at the center of this graph, a broader graph that visualizes connections among thousands of reprinted texts might point to larger, national trends. Who most influenced the nineteenth-century print network? Which publications shared texts most frequently, or to the greatest effect? These are broad versions of the questions I hope network models will help me begin asking of nineteenth-century periodicals in the coming months.

--Ryan Cordell, Northeastern University, r.cordell@neu.edu, @ryancordell

Thursday, August 30, 2012

Mapping the American West

Our project, “Mapping the American West: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches to Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales,” is conceptually indebted to Matthew Wilkins’ “Maps of American Fiction,” which has so far data mined around 300 American novels from the Wright American Fiction Project at Indiana and mapped those locations in an attempt to examine cultural investment in regionalism and internationalism. The scope of our own project is, I think, both more and less ambitious than Wilkins’. Using the same open-source data mining software - Geodict - and ArcGIS, we have so far data mined and mapped locations from two books of Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales. Unlike Wilkins’ project, ours is much more limited in scope. However, to our knowledge, our project is also the first which attempts to synthesize big data processing techniques with close reading. This is the sense in which I believe it is ambitious, as we are working without the guidance of precedents. Some of the difficulties that we have encountered are also emblematic of the problems that graduate students and faculty working without the benefit of digital humanities centers or initiatives at their institutions face when trying to enter into what has been called the “spatial turn” in American Studies.

Daniel and I had never before attempted to use the tools that we employed in this project. We were offered assistance by a close friend who has a degree in urban planning and a deep familiarity with ArcGIS. Together, we were able to experiment with ArcGIS. Unsure of what we would discover along the way, we hoped to be able to offer a critique of both traditional scholarly readings as well as the methodologies for data visualization that are becoming increasingly popular in this field. We wanted to turn our lack of knowledge of these tools and our limited data sample into an advantage, hoping that we might be able to offer some insight that more seasoned DH-ers lack. Though our results are still preliminary, what we have found so far is that from an outsider’s perspective, there seems to be an advantage in using data analysis on small samples where close reading is also possible. In Wilkin’s project, for example, references to locations outside the U.S. are construed as evidence of global awareness; close reading of similar passages reveals them to largely concern immigrant origins as they pertain to Euro-American population composition. The initial purpose of our project (and an ongoing aspect) involves generating new spatial tools that allow a comparison between U.S. expansion in literary texts and the types of infrastructural expansion that allowed its real counterpart. Our most valuable conclusion thus far, however, is that spatial tools are only as good as the theory behind them—without knowing the right questions to ask, the answers are not forthcoming.

We're looking forward to discussing our project with you in October!

Heather Duncan

SUNY Buffalo

Daniel and I had never before attempted to use the tools that we employed in this project. We were offered assistance by a close friend who has a degree in urban planning and a deep familiarity with ArcGIS. Together, we were able to experiment with ArcGIS. Unsure of what we would discover along the way, we hoped to be able to offer a critique of both traditional scholarly readings as well as the methodologies for data visualization that are becoming increasingly popular in this field. We wanted to turn our lack of knowledge of these tools and our limited data sample into an advantage, hoping that we might be able to offer some insight that more seasoned DH-ers lack. Though our results are still preliminary, what we have found so far is that from an outsider’s perspective, there seems to be an advantage in using data analysis on small samples where close reading is also possible. In Wilkin’s project, for example, references to locations outside the U.S. are construed as evidence of global awareness; close reading of similar passages reveals them to largely concern immigrant origins as they pertain to Euro-American population composition. The initial purpose of our project (and an ongoing aspect) involves generating new spatial tools that allow a comparison between U.S. expansion in literary texts and the types of infrastructural expansion that allowed its real counterpart. Our most valuable conclusion thus far, however, is that spatial tools are only as good as the theory behind them—without knowing the right questions to ask, the answers are not forthcoming.

We're looking forward to discussing our project with you in October!

Heather Duncan

SUNY Buffalo

Views from space in the Spatial Turn

In true PechaKucha style, you have only 20 seconds to read this post. Just kidding, I'm not actually timing you.

My presentation is on the spatial relationships of Baltimore's early c19 merchants. Here's an image (from space!) that shows the point of origin for ships that entered Baltimore's ports from March - May 1792.

The markers are weighted: larger markers mean more ships arrived from that port. Baltimore's marker has a black dot in it.

This representation, and others, will help me discuss the trade networks Baltimore's merchants relied on to conduct business. What sorts of questions do you think I can ask and (hopefully) answer with data that looks like this? How is this more or less helpful than a simple list of ports? What does it mean to the historian, or humanist more generally, that he or she can generate a representation like this in only a few hours?

I look forward to responding to your comments and feedback here and at the upcoming conference. Can't wait to be back in Providence!

Abby Schreiber

@abschreiber

My presentation is on the spatial relationships of Baltimore's early c19 merchants. Here's an image (from space!) that shows the point of origin for ships that entered Baltimore's ports from March - May 1792.

|

| Points of Origin for Baltimore Entrances, 1792 |

This representation, and others, will help me discuss the trade networks Baltimore's merchants relied on to conduct business. What sorts of questions do you think I can ask and (hopefully) answer with data that looks like this? How is this more or less helpful than a simple list of ports? What does it mean to the historian, or humanist more generally, that he or she can generate a representation like this in only a few hours?

I look forward to responding to your comments and feedback here and at the upcoming conference. Can't wait to be back in Providence!

Abby Schreiber

@abschreiber

Thursday, August 23, 2012

Digitizing Desire: A History of the Codification of Pleasure

In

the summer of 1938, Theodore Adorno set out for America to head the music

department of the Princeton Radio Project. Upon his arrival, Adorno was proudly

shown the centerpiece of the radio project’s empirical analyses: the

Stanton-Lazarsfeld Analyzer. Designed by social scientist Paul Lazarsfeld and

CBS executive Frank Stanton, the Analyzer included a green “like” and a red

“dislike” button. As music was piped into the different rooms of the project,

volunteers of different age, race and class were instructed to press the red or

green button every few seconds depending on whether

they liked what they were hearing at that moment or not. Codifying the analog

rhythm of music into binary pulses of like and dislike, the Analyzer was

digitizing desire.

Be

it

the measurement of happiness according to Twitter tweets, Facebook

likes

(but not dislikes) or the ubiquitous internet star rating of everything

from

blockbuster films to vacuum cleaners, our wants and pleasures are

constantly

being translated into a stream of digitized ones and zeroes. Tracing the

origins of today’s digitization of desire, the paper I will be

presenting in October uses

the Princeton Radio Project to explore how groundbreaking intellectual

and

cultural developments such as behavioral psychology, neoclassical

economics and consumer capitalism played a crucial role in creating the

rating-obsessed world we live

in today.

I’d

be happy to receive any comments (or a star rating 1 thru 5) and look forward to meeting you all soon!

Eli

Graduate student in Harvard University's American Studies program

All I Need to Know About Birtherism I Learned from the “Feejee Mermaid”: Audience Reception and Interrogating Truth Claims in Communications Revolutions

NB: My week to post to the blog was the same week that I 1) had my comprehensive exams and 2) got married, and in the confusion, I forgot to post. For this reason, I am postdating and putting this up now in hopes of getting feedback before the conference.

United States History has in many ways been singularly defined by a long series of communications revolutions. From the First Amendment and the Postal Road System to the telegraph to the birth of the Railway Mail Service to the rise of the mass media to the Internet, the United States has been a nation that has been constantly being reshaped by revolutionary shifts in communications. The way that people communicate has been shifting rapidly and radically for most of our nation's history. This paper looks at the way that these communications revolutions have encouraged audiences to constantly retrain themselves to discern between counterfeit and authentic, to critically interrogate new information and attempt to detect deception-- and how this sort of interrogation has become a recurring form of entertainment and ludic pleasure.

PT Barnum is perhaps best known for his apocryphal dictum that “there’s a sucker born every minute,” but investigating Barnum’s audience suggests that they were far savvier and less trusting than is popularly assumed. James Cook, in his The Arts of Deception, demonstrates quite well that Barnum based much of his career on a winking playfulness with his audience, one based on constantly dancing on the line between the authentic and deception. This playfulness with truth claims, far from going unnoticed by his audience, was one of the primary things that appealed to Barnum’s audience. Witnessing exhibitions of the “Feejee Mermaid,” George Washington’s 161-year-old nursemaid Joice Heth, or the nondescript “What Is It?”, audiences went to witness uncertain “objects,” to interrogate the truth claims of exhibitors and the surrounding media, and to attempt to determine for themselves if they were being deceived or not. The playful negotiation of truth and fiction was a large part of the audience’s enjoyment, in a time of intense technological and media shifts, from the age of Jackson to the twentieth century.

Likewise, while many popular and academic accounts of Internet users assume that they are a deeply uncritical audience, I argue that much the same process of playful interrogation of authentic versus counterfeit still goes on on-line, and that it is indeed a very popular type of discourse on the web. Looking at examples including the 4chan “Perfection Girl” meme, “Slender Man,” and Youtube trick-photography videos, I argue that Internet users are playing with one another, making a game of critical analysis. Of course, in an age of deep epistemological uncertainty, “truth” is a far more problematic category today than it was in the nineteenth century. For this reason, I extend my analysis to the Korean <Tablo Online> movement, as well as the 9-11 Truther and Birther movements in the United States. While these online movements deal with far more serious issues-- and while the conclusions they come to are deeply problematic-- the mode of discourse within them and the methods by which they interrogate evidence is fundamentally very similar to the game-like mechanics with which Internet users play at questions of veracity. I argue that this is fundamental to the popularity and longevity of these conspiracy-theory based movements, and can provide insight into the way authenticity and deception are understood in the twenty-first century.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

African Passages, Lowcountry Adaptations: Transforming Charleston’s Public History Landscape through a Digital Exhibition Project

Looking back now at the title of our presentation, I’m realizing that our claim that a digital exhibition can change Charleston’s public history landscape seems pretty bold. In many ways though, I think we are at least onto something-- I do believe the relationship between inclusive public history work and digital humanities research and resources could be greatly expanded, and even transformative, for Charleston and the Lowcountry region. To provide some context, for over a century, since tourism first became a lucrative industry in the Charleston area in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, historic sites, tour guides, and museums have overwhelmingly focused on antebellum and colonial white elite experiences and material culture. Their interpretation choices served to marginalize or romanticize historic social struggles over race, labor, and citizenship that formed during and after slavery in this region, and continued into twentieth century civil rights activism. Today, “Historic Charleston” is a multi-billion dollar tourism destination that receives over four million visitors annually. But with some notable exceptions, most historic tourism producers still do not frame African American history during and after slavery as central to understanding Lowcountry history. Instead, guides give these subjects passing acknowledgement, or historic sites present them as separate, optional additions to their standard white elite tour narratives.

Acknowledging and effectively interpreting Charleston’s full history to the public is long overdue, but cultural institutions, historic sites, and tour guides face major challenges for accomplishing this task. For example, the physical presence of historic mansions of elite whites often dominate current Lowcountry historic landscapes and guide narratives, while complex social histories of African American labor and struggle within these spaces or on surrounding former rice fields can be more difficult for visitors to conceptualize. In addition, efforts to build new physical exhibitions and museum structures to address these underrepresented histories often become constrained by limited budgets in the current economy. In this context, mobile applications and online exhibitions can engage multimedia archival materials and scholarly research to help users effectively visualize and connect with more diverse social histories, within a fuller range of the Lowcountry’s historic structures and landscapes. They can also accomplish this at minimal costs and impacts on the current physical environments and communities living within these spaces. Through African Passages, Lowcountry Adaptations, the Lowcountry Digital Library will specifically introduce a cohesive online narrative platform for presenting digital projects connected to the history of colonial and antebellum slavery in this region (such as online tours of specific spaces where enslaved people lived and work in the Lowcountry, or images of artifacts they used). Our goal is for this online exhibition to promote greater understanding and appreciation for this region’s complex, multicultural histories to a range of user audiences, including visitors, locals, scholars and educators, as well as tour guides.

Mary Battle, PhD Candidate

Emory University

Assistant Digital Curator

Lowcountry Digital Library

College of Charleston

Acknowledging and effectively interpreting Charleston’s full history to the public is long overdue, but cultural institutions, historic sites, and tour guides face major challenges for accomplishing this task. For example, the physical presence of historic mansions of elite whites often dominate current Lowcountry historic landscapes and guide narratives, while complex social histories of African American labor and struggle within these spaces or on surrounding former rice fields can be more difficult for visitors to conceptualize. In addition, efforts to build new physical exhibitions and museum structures to address these underrepresented histories often become constrained by limited budgets in the current economy. In this context, mobile applications and online exhibitions can engage multimedia archival materials and scholarly research to help users effectively visualize and connect with more diverse social histories, within a fuller range of the Lowcountry’s historic structures and landscapes. They can also accomplish this at minimal costs and impacts on the current physical environments and communities living within these spaces. Through African Passages, Lowcountry Adaptations, the Lowcountry Digital Library will specifically introduce a cohesive online narrative platform for presenting digital projects connected to the history of colonial and antebellum slavery in this region (such as online tours of specific spaces where enslaved people lived and work in the Lowcountry, or images of artifacts they used). Our goal is for this online exhibition to promote greater understanding and appreciation for this region’s complex, multicultural histories to a range of user audiences, including visitors, locals, scholars and educators, as well as tour guides.

Mary Battle, PhD Candidate

Emory University

Assistant Digital Curator

Lowcountry Digital Library

College of Charleston

Monday, August 6, 2012

Excavating Before 1970

One of the challenges or research in the digital age is locating and accessing texts written prior to 1970 that are not commonly used. Archives are increasingly adding to online digital documents in an effort to preserve the most valuable primary source materials. In the process, manuscripts are privileged over less snazzy (and more lengthy) old books. For my own research on theatre and dance histories these old books contain a plethora of information about play productions and period perspectives. Generally speaking, books between 1890 and 1970 get lost in the catalogue since many collections began to digitize new acquisitions around 1970. Accessing these materials is still a challenge of the digital age, and when I am able to find a volume (such as Robert Albion's History of the New York Port), it can be easier to purchase online than to acquire through library or archival sources.

My own project "Tracing Ira Aldridge, " lies at the other end of the spectrum. Through a digital tool called MixD I am attempting to construct through mapping and photo references the performance journeys of 19th century actors. Even as I invest in data collection and sorting for realizing the visual display of graphics and information, I wonder what the accessibility of this material will be for those who want to access this tool outside of the digital world.

Posted by

Anita Gonzalez, Professor

State University of New York at New Paltz

gonzalea@newpaltz.edu

Friday, August 3, 2012

Conference registration, program now online

The main NEASA page has just been updated with a link to the program. To register, click here.

Wednesday, August 1, 2012

The misread professor

One story: when I was teaching a 4-4 composition load, I had a conversation with a father's friend, who asked me how many courses I taught. 4, I said. How many hours a week does each class meet? 3, I said. "So you work 12 hours a week!" he said. At that point, teaching courses that required multiple drafts, I was working closer to 12 hours a day (almost every day of the week). Recently, David C. Levy wrote in the Washington Post, how underworked and overpaid professors were. As others noted, not only did this article underestimate how much work teaching is, it ignored all the service work we do, for one, and eschewed all ranks of professor below full, including adjuncts.

Our panel is less formal and purely academic than most of the ones here (perhaps all of them). It involves the weird lives as professors we lead, semi-public, sometimes unconventional, and often (or even almost always) misinterpreted.

There are far bigger issues facing the professoriate--finding a good job, decreasing tenure rates, racial and gender discrimination, and changing workload expectations. But our perceived place in American culture have an impact on almost all of those issues and so by extension, being misread is important.

Part of the reason for this consistent misreading is the partially public lives we have as professors--we spend 6 to 12 hours a week performing teaching and another 3 to 6 in office hours. But the rest of the work we do is often private or straddles the line between public and private, and often done, in fact, in odd hours and wherever we want. That means male professors can sometimes help with child care, and many of us can do our errands at odd hours, though not without questions.

No one likes a pity party about how hard a professor's life is, and we do have more autonomy and better working conditions than many professions. But without a better understanding of what professors do, those outside the profession will continue to misread us.

--Jonathan Silverman

Our panel is less formal and purely academic than most of the ones here (perhaps all of them). It involves the weird lives as professors we lead, semi-public, sometimes unconventional, and often (or even almost always) misinterpreted.

There are far bigger issues facing the professoriate--finding a good job, decreasing tenure rates, racial and gender discrimination, and changing workload expectations. But our perceived place in American culture have an impact on almost all of those issues and so by extension, being misread is important.

Part of the reason for this consistent misreading is the partially public lives we have as professors--we spend 6 to 12 hours a week performing teaching and another 3 to 6 in office hours. But the rest of the work we do is often private or straddles the line between public and private, and often done, in fact, in odd hours and wherever we want. That means male professors can sometimes help with child care, and many of us can do our errands at odd hours, though not without questions.

No one likes a pity party about how hard a professor's life is, and we do have more autonomy and better working conditions than many professions. But without a better understanding of what professors do, those outside the profession will continue to misread us.

--Jonathan Silverman

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Crosspost: Scholarly Research and Writing in the Digital Age

Hi everyone--

Check out this post on scholarly research and writing on Steven Lubar's blog (he's our keynote speaker): http://stevenlubar.wordpress.com/2012/07/22/scholarly-research-and-writing-in-the-digital-age/

--Jonathan Silverman

--Jonathan Silverman

Monday, July 23, 2012

Facebook: A 21st Century Scrapbook

While researching scrapbook as an autobiographical medium, I encountered the following Salman Rushdie quote:

"But human beings do not perceive things whole; we are not gods but wounded creatures, cracked lenses, capable only of fractured perceptions. Partial beings, in all the sense of that phrase. Meaning is a shaky edifice we build out of scraps, dogmas, childhood injuries, newspaper articles, chance remarks, old films, small victories, people hated, people loved; perhaps it is because our sense of what is the case is constructed from such inadequate materials that we defend it so fiercely, even to the death."

This is, in my mind, the perfect summary of the autobiographical act, a collection of odds and ends, bits and pieces, the random scraps that are stored in one's memory and assigned a degree of importance. Every bit as significant are those pieces that are are dismissed. What is held onto and what is cast away, each is a vital part of the construction of one's self-curated self-history.

These parts of a whole were, for centuries, recorded on paper, a combination of text and imagery. Today, they are uploaded via mobile phones to Facebook.

Ellen Litwicki

SUNY Fredonia

In October I will speaking about the historical continuity between scrapbooks and Facebook, and time permitting will also venture into the following topics, all of which are in the paper from which I am drawing my presentation:

•The ever changing nature of "new media"

•The role of print culture, mass publication, the rise of "scrap"

•Cellophane tape and the opportunities it offered for preservation or memories

•Polaroid vs. Instagram

If anyone is interested in discussing any of these topics further, feel free to get in touch with me.--Lucinda Hannington

Saturday, July 21, 2012

Tea Time in the Digital Age: Self-Produced Media and the Tea Party Movement

The Tea Party Movement in the contemporary United States

thrives on new media technologies. Despite its activists' apparent inclination

toward the past—demonstrated by a predilection for three-cornered hats and

petticoats, a veneration of the U.S. Constitution and other founding documents,

and the popular slogan“I want my America back"—the movement is actually at the

forefront of digital and political modernity. Utilizing social media and a

variety of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has allowed the

movement to organize, mobilize, and share information much more broadly and

rapidly than could have been possible several years ago. This has given rise to

a novel organizational structural formation that is neither purely hierarchical

nor wholly grassroots, neither truly local nor entirely national in scope. Based

on ethnographic fieldwork among Tea Party activists in Connecticut, my upcoming

NEASA talk will explore the modes and meanings of digital media production and

its impact on the movement as a whole.

Tea Party activists are highly prolific in producing and

sharing digital information, including documentation, commentary, and analysis

of their own rallies and other events. The production of digital self-mediation

is often instantaneous, as activists post photographs, videos, and commentary

online with their phones while the rallies are still going on. One Connecticut activist

in particular has taken it upon himself to document and publicize almost

everything that Tea Party activists have done throughout the state since the

movement began in early 2009. His YouTube channel has become a massive digital

video archive composed of almost 1,400 videos, with more added every week. Another

has begun producing his own TV show which streams live on his website every

Thursday night. Other forms of self-produced digital media include analytical

or investigative essays posted on personal blogs and shared on social media

platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

But the digital revolution's centrality to the Tea Party’s

emergence and continued development does not rest only on its capabilities for hyper-connectivity

and enhanced communication. In a social world in which the "mainstream media" cannot be trusted—as one Tea Party interlocutor put it: “We're tired of being

lied to, and were tired of being lied about”—the ability to represent

themselves on such a large scale has been experienced by activists as an

important mechanism of rebellion and self-empowerment. In fact, the desire for

self-representation and self-empowerment are in many ways equivalent, and

constitute a fundamental drive of the movement itself.

In order to better understand these processes, my NEASA talk will investigate the ways that Tea Party political subjectivity is

explored and, in many ways, instantiated through media practices in the digital

age. It will trace how the ongoing process of self-mediation, largely enabled

by digital ICTs, is one of the primary means whereby activists consider

themselves to be engaging in meaningful revolutionary action.

--Sierra Bell

Thursday, July 12, 2012

The Digital Revolution and the Problem of Context

As a scholar and teacher working at a small university with

a limited library, I embrace the worlds that the digital revolution has opened

for both researchers and students. The growing array of digitized sources, from

political documents to personal letters, and from art to vintage

advertisements, has provided a multiplicity of new avenues for creative

assignments that engage history students with primary source materials. And for

a scholar who slogged through countless rolls of microfilmed newspapers for my

first book on holidays, the ability to do full text searches in historical

newspaper, magazine, diary, and letter databases is sheer heaven.

Despite all this, I have some reservations about the digital

cornucopia. For one thing, the serendipitous find while plodding through a

diary or reels of microfilm has been (virtually) eliminated. As a historian, however,

I worry most about the loss of both historical context and what might be called

the physicality of history. To take the second issue first, just as art

historians know that looking at a digital image is nothing like looking at the

actual work of art, so looking at a digitized diary or dress is a poor

substitute for holding said artifact in one’s hands. I can show my students

dozens of digitized calling cards, but it just doesn’t provide the same glimpse

into Victorian lives as would seeing and handling the actual cards in the

scrapbooks where women pasted them next to other mementoes.

The scrapbooks begin to provide the material context of

these historical artifacts. There are many wonderful web sites that do include

a good deal of physical, historical, and/or contextual information on their

digitized images, but there are, nevertheless, countless digital “orphans” out

there as well. Moreover, the methods of online searching can easily slight

historical context. For instance, when I can full-text search to find every

mention of birthday or wedding gifts in a group of diaries, this is a boon to

my research on gift giving. Yet it has the potential to privilege quantity over

quality and insight into the larger context of lives. Why did Daniel give Edna

a gift for her birthday? Who was he, and how did he fit into Edna’s life? Was

he a beau, a brother, a neighbor? Why did he give one kind of gift and not

another? To begin to answer such questions, we have to read well beyond the

paragraph on Edna’s birthday gifts.

As a professional historian, I am, of course, much better

equipped and more motivated than my students to fill in the context of my digital

sources, and I also have more opportunities to study actual documents and

artifacts. My conference paper will explore some ways to introduce more

opportunities for students to experience the physical side of history, as well

as ways to help students restore some of the historical context to digital

“orphans.”

SUNY Fredonia

Sunday, July 8, 2012

Roving Mars: The Next Frontier of Space and Media

Mars has inspired

dreamers and space enthusiasts as the next logical step after going to the

moon. In 1998, the Mars Pathfinder

mission captured public attention by demonstrating the first beloved rover

(Sojourner) to travel the surface, leading to the later Mars Exploration Rover

program (Spirit and Opportunity that landed in 2004).

The Mars Pathfinder mission reveals a significant

shift in the relationship between the scientists and the public, which

traditionally used science journalists as an intermediary to

convey information through the mass media. During earlier missions, the public primarily heard about space news from science journalists; these stories included their spin and any conclusions about why it might be important to the reader. The

mission’s public affairs staff also provided a press release and supporting data, as

well as photographs, to the journalists for distribution through mass media

outlets. Mars Pathfinder made a groundbreaking transition into digital media,

becoming a record setting web event with more than half a million hits

surrounding its landing. The web event illustrated direct public interest in

the mission and would fundamentally reshape how future missions started communicating their news through websites and listservs. The Mars Exploration Rovers would further engage the public though more sophisticated websites and

social media.

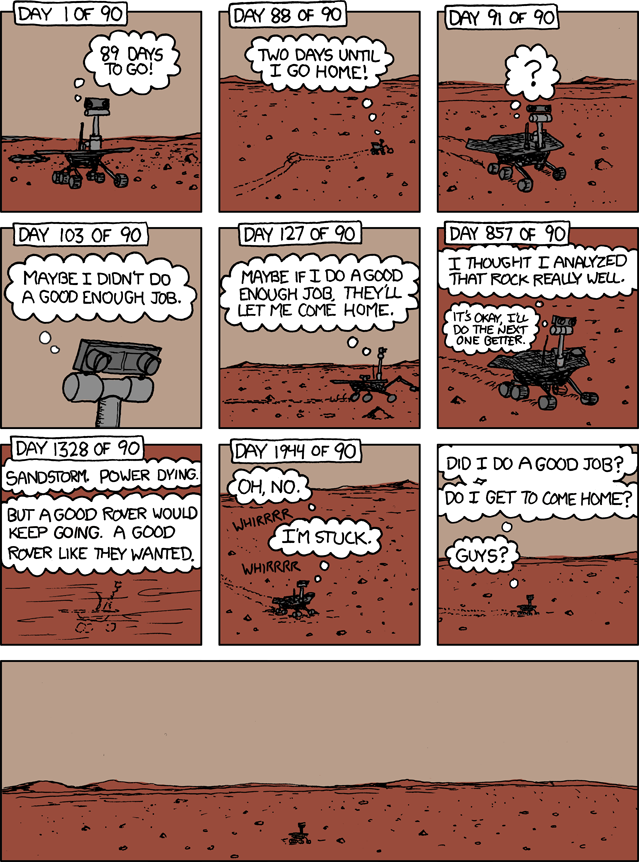

The following xkcd webcomic provides an excellent example of how the rovers captured the hearts and minds of the public:

By Giny Cheong

Tuesday, July 3, 2012

The Digital Approach and the Globalization of Art Historical Discourses. A Case Study: Jackson Pollock in Postwar Europe

The project I will present at the

2012 NEASA Conference is part of Artl@s. Launched

in 2009 at the École normale supérieure in Paris, Artl@s aims at promoting a geo-social and transnational

history of the arts that meets the challenge of

spatial and digital humanities. It brings together scholars eager to embrace

digital technology to share, process, and visualize socio-historical data. Artl@s provides them with the tools and

support to achieve a dynamic and total history of the arts, namely a database,

BasArt; a working space, Artl@s

Worksite; a publishing interface, Artl@s

Website; and a collection of interactive books, Artl@s

Publications. The underlying ambition of Artl@s

is to participate in the redefinition of the discipline after the spatial,

global, and digital turns, help scholars rethink and adapt their practices in

this new intellectual environment, and educate and empower the public. At the

core of the project is the belief that a spatial approach is a means to

contribute to a truly global history of the arts and to partake in one of the

most important characteristics of the digital revolution: learning by sharing.

My own contribution to Artl@s considers the diffusion of American art in postwar Western Europe. Thanks to the generous support of the Vice President of Research at Purdue University, I was able to bring together a multidisciplinary team that includes two of my colleagues Christopher Miller, a geoinformatics expert in charge of the Purdue GIS Library, and Sorin A. Matei, a digital humanity specialist creator of Visible Past, a georeferenced online content management. The project focuses on exhibitions that took place between 1945 and 1970 and that featured works by American Abstract Expressionist and American Pop artists. The results of this research will be featured on an interactive web application that will allow users to view the maps, zoom in on them, select artists or artworks, scroll through dates, and even create their own maps. It will thus be a great tool for scholars, students, and museums professionals, who will be able to use it as a starting point for their own investigations.

At the 2012 NEASA Conference, I will take the reception of Jackson Pollock in postwar Europe as a case study. I will describe the process of transforming the analog information available on this artist into relational database, which is then used to generate dynamic maps and statistics. I hope to demonstrate how those maps and charts not only summarize and visualize information, but also how they expose new information that allow me to challenge the official story of postwar American art.

By Catherine Dossin

My own contribution to Artl@s considers the diffusion of American art in postwar Western Europe. Thanks to the generous support of the Vice President of Research at Purdue University, I was able to bring together a multidisciplinary team that includes two of my colleagues Christopher Miller, a geoinformatics expert in charge of the Purdue GIS Library, and Sorin A. Matei, a digital humanity specialist creator of Visible Past, a georeferenced online content management. The project focuses on exhibitions that took place between 1945 and 1970 and that featured works by American Abstract Expressionist and American Pop artists. The results of this research will be featured on an interactive web application that will allow users to view the maps, zoom in on them, select artists or artworks, scroll through dates, and even create their own maps. It will thus be a great tool for scholars, students, and museums professionals, who will be able to use it as a starting point for their own investigations.

At the 2012 NEASA Conference, I will take the reception of Jackson Pollock in postwar Europe as a case study. I will describe the process of transforming the analog information available on this artist into relational database, which is then used to generate dynamic maps and statistics. I hope to demonstrate how those maps and charts not only summarize and visualize information, but also how they expose new information that allow me to challenge the official story of postwar American art.

By Catherine Dossin

Monday, July 2, 2012

Word and Image in the Print Culture of Atlantic Slave Revolt

The paper I will present at the NEASA conference this fall attempts to theorize the relationship between prose narrative accounts of Atlantic slave revolt and the illustrations that often accompanied them. Approaching the Nat Turner insurrection (1831) through the lens of media studies, I examine the tensions that exist between the content of these written accounts, which tend to emphasize the contingent and exceptional nature of violent slave uprisings—and thus the impossibility of their recurrence—and the discursive thrust of their frontispiece illustrations, which often undercuts this attempted containment. The genericized woodblock images that precede these pamphlets often operate by an allegorical logic that undermines the text’s overall efforts to render the Turner revolt a singular phenomenon. Moreover, the images’ technological reproducibility—emblematized by the fact that the image accompanying Samuel Warner’s Authentic and Impartial Narrative (1831) of the Turner revolt is recycled in an account of an entirely different uprising during the Seminole War several years later (the anonymous Authentic Narrative of the Seminole War, 1836)—gives the ultimate lie to claims to insurrectionary exceptionalism.

I am still working to verify my hypotheses about the kinds of printing networks that would have permitted the woodblocks used to create these images to migrate between the different urban hubs of antebellum printing (I have determined that the images are not merely copies of each other). As I do so, it would be very helpful to know if others involved in this year’s conference are addressing similar issues through different materials and how they are approaching them. I would be interested to hear about other projects that attempt to trace the provenance of shared printed matter and then to leverage this information into an argument about the literary or ideological content of texts.

The second question I would like to pose here involves how digital archives are making different kinds of scholarship possible. As my paper will detail, this project would not have been possible without both expansive online research into the visual culture of Atlantic slave revolt (which rendered the recycling alluded to above visible to me) and more traditional archival research (which confirmed it). Likewise, digital remediation will make it infinitely easier for me to communicate my findings at our conference and in the classroom. At the same time, it would be naïve to regard such remediations as substantially different from the ones that take place between the different texts I mention. If the tools of digital literary studies have become sophisticated enough to generate new readings of old texts, how can they also help us to view our own scholarly and pedagogical practices in new lights?

I am still working to verify my hypotheses about the kinds of printing networks that would have permitted the woodblocks used to create these images to migrate between the different urban hubs of antebellum printing (I have determined that the images are not merely copies of each other). As I do so, it would be very helpful to know if others involved in this year’s conference are addressing similar issues through different materials and how they are approaching them. I would be interested to hear about other projects that attempt to trace the provenance of shared printed matter and then to leverage this information into an argument about the literary or ideological content of texts.

The second question I would like to pose here involves how digital archives are making different kinds of scholarship possible. As my paper will detail, this project would not have been possible without both expansive online research into the visual culture of Atlantic slave revolt (which rendered the recycling alluded to above visible to me) and more traditional archival research (which confirmed it). Likewise, digital remediation will make it infinitely easier for me to communicate my findings at our conference and in the classroom. At the same time, it would be naïve to regard such remediations as substantially different from the ones that take place between the different texts I mention. If the tools of digital literary studies have become sophisticated enough to generate new readings of old texts, how can they also help us to view our own scholarly and pedagogical practices in new lights?

-Alex Mazzaferro

Friday, June 29, 2012

Sample post: Horse racing and order

What I'm working on right now are questions about order in architecture and public spaces, especially as they relate to horse racing. My larger project is a semiotic explanation of what horse racing communicates to us through its various signs, and lately, I've been thinking more about how much of horse racing is about the balance between order and disorder at racetracks.

It seems to me that almost everything at a racetrack is a reaction to the disorder seemingly naturally attached to sports, gambling, and class--the track to contain horses, the racing form to make sense of a confusing array of factors that are supposed to help the gambler choose her horse, and the seating designed to separate classes (even as they inevitably mix). The above photo shows how Saratoga adds fashion requirements to its clubhouse seating.

This could be taken as a type of bigger metaphor for our culture at large (which is the larger argument I'm trying to make). I'm working through sources in architecture, psychology, and sociology in order to help my argument.

The dress code for the Saratoga Race Course clubhouse.

It seems to me that almost everything at a racetrack is a reaction to the disorder seemingly naturally attached to sports, gambling, and class--the track to contain horses, the racing form to make sense of a confusing array of factors that are supposed to help the gambler choose her horse, and the seating designed to separate classes (even as they inevitably mix). The above photo shows how Saratoga adds fashion requirements to its clubhouse seating.

This could be taken as a type of bigger metaphor for our culture at large (which is the larger argument I'm trying to make). I'm working through sources in architecture, psychology, and sociology in order to help my argument.

--Jonathan Silverman

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.png)