Hi everyone--

Check out this post on scholarly research and writing on Steven Lubar's blog (he's our keynote speaker): http://stevenlubar.wordpress.com/2012/07/22/scholarly-research-and-writing-in-the-digital-age/

--Jonathan Silverman

Welcome to the Pre-Conference Conversations for the New England American Studies Conference. We're writing about the things we'll talk about the conference--join the conversation!

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Monday, July 23, 2012

Facebook: A 21st Century Scrapbook

While researching scrapbook as an autobiographical medium, I encountered the following Salman Rushdie quote:

"But human beings do not perceive things whole; we are not gods but wounded creatures, cracked lenses, capable only of fractured perceptions. Partial beings, in all the sense of that phrase. Meaning is a shaky edifice we build out of scraps, dogmas, childhood injuries, newspaper articles, chance remarks, old films, small victories, people hated, people loved; perhaps it is because our sense of what is the case is constructed from such inadequate materials that we defend it so fiercely, even to the death."

This is, in my mind, the perfect summary of the autobiographical act, a collection of odds and ends, bits and pieces, the random scraps that are stored in one's memory and assigned a degree of importance. Every bit as significant are those pieces that are are dismissed. What is held onto and what is cast away, each is a vital part of the construction of one's self-curated self-history.

These parts of a whole were, for centuries, recorded on paper, a combination of text and imagery. Today, they are uploaded via mobile phones to Facebook.

Ellen Litwicki

SUNY Fredonia

In October I will speaking about the historical continuity between scrapbooks and Facebook, and time permitting will also venture into the following topics, all of which are in the paper from which I am drawing my presentation:

•The ever changing nature of "new media"

•The role of print culture, mass publication, the rise of "scrap"

•Cellophane tape and the opportunities it offered for preservation or memories

•Polaroid vs. Instagram

If anyone is interested in discussing any of these topics further, feel free to get in touch with me.--Lucinda Hannington

Saturday, July 21, 2012

Tea Time in the Digital Age: Self-Produced Media and the Tea Party Movement

The Tea Party Movement in the contemporary United States

thrives on new media technologies. Despite its activists' apparent inclination

toward the past—demonstrated by a predilection for three-cornered hats and

petticoats, a veneration of the U.S. Constitution and other founding documents,

and the popular slogan“I want my America back"—the movement is actually at the

forefront of digital and political modernity. Utilizing social media and a

variety of information and communication technologies (ICTs) has allowed the

movement to organize, mobilize, and share information much more broadly and

rapidly than could have been possible several years ago. This has given rise to

a novel organizational structural formation that is neither purely hierarchical

nor wholly grassroots, neither truly local nor entirely national in scope. Based

on ethnographic fieldwork among Tea Party activists in Connecticut, my upcoming

NEASA talk will explore the modes and meanings of digital media production and

its impact on the movement as a whole.

Tea Party activists are highly prolific in producing and

sharing digital information, including documentation, commentary, and analysis

of their own rallies and other events. The production of digital self-mediation

is often instantaneous, as activists post photographs, videos, and commentary

online with their phones while the rallies are still going on. One Connecticut activist

in particular has taken it upon himself to document and publicize almost

everything that Tea Party activists have done throughout the state since the

movement began in early 2009. His YouTube channel has become a massive digital

video archive composed of almost 1,400 videos, with more added every week. Another

has begun producing his own TV show which streams live on his website every

Thursday night. Other forms of self-produced digital media include analytical

or investigative essays posted on personal blogs and shared on social media

platforms like Facebook and Twitter.

But the digital revolution's centrality to the Tea Party’s

emergence and continued development does not rest only on its capabilities for hyper-connectivity

and enhanced communication. In a social world in which the "mainstream media" cannot be trusted—as one Tea Party interlocutor put it: “We're tired of being

lied to, and were tired of being lied about”—the ability to represent

themselves on such a large scale has been experienced by activists as an

important mechanism of rebellion and self-empowerment. In fact, the desire for

self-representation and self-empowerment are in many ways equivalent, and

constitute a fundamental drive of the movement itself.

In order to better understand these processes, my NEASA talk will investigate the ways that Tea Party political subjectivity is

explored and, in many ways, instantiated through media practices in the digital

age. It will trace how the ongoing process of self-mediation, largely enabled

by digital ICTs, is one of the primary means whereby activists consider

themselves to be engaging in meaningful revolutionary action.

--Sierra Bell

Thursday, July 12, 2012

The Digital Revolution and the Problem of Context

As a scholar and teacher working at a small university with

a limited library, I embrace the worlds that the digital revolution has opened

for both researchers and students. The growing array of digitized sources, from

political documents to personal letters, and from art to vintage

advertisements, has provided a multiplicity of new avenues for creative

assignments that engage history students with primary source materials. And for

a scholar who slogged through countless rolls of microfilmed newspapers for my

first book on holidays, the ability to do full text searches in historical

newspaper, magazine, diary, and letter databases is sheer heaven.

Despite all this, I have some reservations about the digital

cornucopia. For one thing, the serendipitous find while plodding through a

diary or reels of microfilm has been (virtually) eliminated. As a historian, however,

I worry most about the loss of both historical context and what might be called

the physicality of history. To take the second issue first, just as art

historians know that looking at a digital image is nothing like looking at the

actual work of art, so looking at a digitized diary or dress is a poor

substitute for holding said artifact in one’s hands. I can show my students

dozens of digitized calling cards, but it just doesn’t provide the same glimpse

into Victorian lives as would seeing and handling the actual cards in the

scrapbooks where women pasted them next to other mementoes.

The scrapbooks begin to provide the material context of

these historical artifacts. There are many wonderful web sites that do include

a good deal of physical, historical, and/or contextual information on their

digitized images, but there are, nevertheless, countless digital “orphans” out

there as well. Moreover, the methods of online searching can easily slight

historical context. For instance, when I can full-text search to find every

mention of birthday or wedding gifts in a group of diaries, this is a boon to

my research on gift giving. Yet it has the potential to privilege quantity over

quality and insight into the larger context of lives. Why did Daniel give Edna

a gift for her birthday? Who was he, and how did he fit into Edna’s life? Was

he a beau, a brother, a neighbor? Why did he give one kind of gift and not

another? To begin to answer such questions, we have to read well beyond the

paragraph on Edna’s birthday gifts.

As a professional historian, I am, of course, much better

equipped and more motivated than my students to fill in the context of my digital

sources, and I also have more opportunities to study actual documents and

artifacts. My conference paper will explore some ways to introduce more

opportunities for students to experience the physical side of history, as well

as ways to help students restore some of the historical context to digital

“orphans.”

SUNY Fredonia

Sunday, July 8, 2012

Roving Mars: The Next Frontier of Space and Media

Mars has inspired

dreamers and space enthusiasts as the next logical step after going to the

moon. In 1998, the Mars Pathfinder

mission captured public attention by demonstrating the first beloved rover

(Sojourner) to travel the surface, leading to the later Mars Exploration Rover

program (Spirit and Opportunity that landed in 2004).

The Mars Pathfinder mission reveals a significant

shift in the relationship between the scientists and the public, which

traditionally used science journalists as an intermediary to

convey information through the mass media. During earlier missions, the public primarily heard about space news from science journalists; these stories included their spin and any conclusions about why it might be important to the reader. The

mission’s public affairs staff also provided a press release and supporting data, as

well as photographs, to the journalists for distribution through mass media

outlets. Mars Pathfinder made a groundbreaking transition into digital media,

becoming a record setting web event with more than half a million hits

surrounding its landing. The web event illustrated direct public interest in

the mission and would fundamentally reshape how future missions started communicating their news through websites and listservs. The Mars Exploration Rovers would further engage the public though more sophisticated websites and

social media.

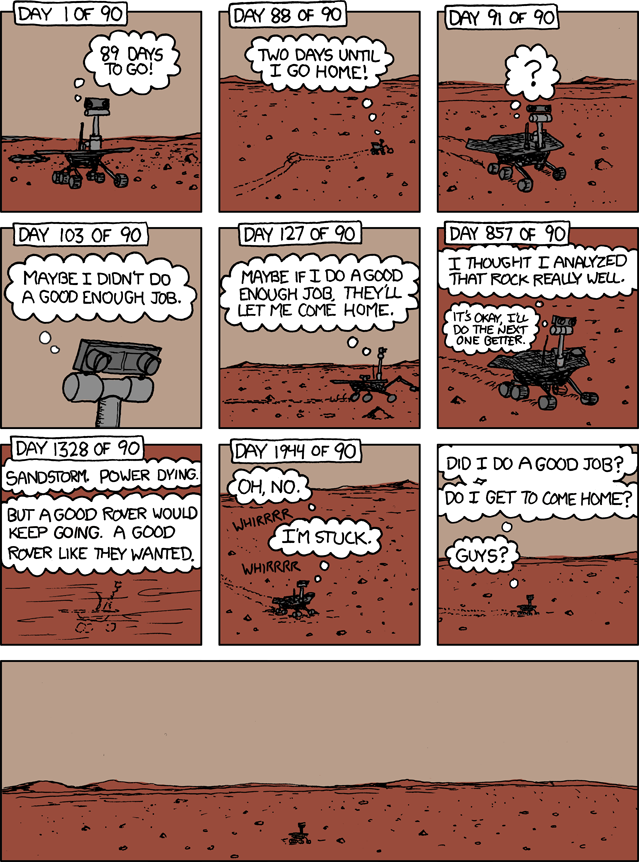

The following xkcd webcomic provides an excellent example of how the rovers captured the hearts and minds of the public:

By Giny Cheong

Tuesday, July 3, 2012

The Digital Approach and the Globalization of Art Historical Discourses. A Case Study: Jackson Pollock in Postwar Europe

The project I will present at the

2012 NEASA Conference is part of Artl@s. Launched

in 2009 at the École normale supérieure in Paris, Artl@s aims at promoting a geo-social and transnational

history of the arts that meets the challenge of

spatial and digital humanities. It brings together scholars eager to embrace

digital technology to share, process, and visualize socio-historical data. Artl@s provides them with the tools and

support to achieve a dynamic and total history of the arts, namely a database,

BasArt; a working space, Artl@s

Worksite; a publishing interface, Artl@s

Website; and a collection of interactive books, Artl@s

Publications. The underlying ambition of Artl@s

is to participate in the redefinition of the discipline after the spatial,

global, and digital turns, help scholars rethink and adapt their practices in

this new intellectual environment, and educate and empower the public. At the

core of the project is the belief that a spatial approach is a means to

contribute to a truly global history of the arts and to partake in one of the

most important characteristics of the digital revolution: learning by sharing.

My own contribution to Artl@s considers the diffusion of American art in postwar Western Europe. Thanks to the generous support of the Vice President of Research at Purdue University, I was able to bring together a multidisciplinary team that includes two of my colleagues Christopher Miller, a geoinformatics expert in charge of the Purdue GIS Library, and Sorin A. Matei, a digital humanity specialist creator of Visible Past, a georeferenced online content management. The project focuses on exhibitions that took place between 1945 and 1970 and that featured works by American Abstract Expressionist and American Pop artists. The results of this research will be featured on an interactive web application that will allow users to view the maps, zoom in on them, select artists or artworks, scroll through dates, and even create their own maps. It will thus be a great tool for scholars, students, and museums professionals, who will be able to use it as a starting point for their own investigations.

At the 2012 NEASA Conference, I will take the reception of Jackson Pollock in postwar Europe as a case study. I will describe the process of transforming the analog information available on this artist into relational database, which is then used to generate dynamic maps and statistics. I hope to demonstrate how those maps and charts not only summarize and visualize information, but also how they expose new information that allow me to challenge the official story of postwar American art.

By Catherine Dossin

My own contribution to Artl@s considers the diffusion of American art in postwar Western Europe. Thanks to the generous support of the Vice President of Research at Purdue University, I was able to bring together a multidisciplinary team that includes two of my colleagues Christopher Miller, a geoinformatics expert in charge of the Purdue GIS Library, and Sorin A. Matei, a digital humanity specialist creator of Visible Past, a georeferenced online content management. The project focuses on exhibitions that took place between 1945 and 1970 and that featured works by American Abstract Expressionist and American Pop artists. The results of this research will be featured on an interactive web application that will allow users to view the maps, zoom in on them, select artists or artworks, scroll through dates, and even create their own maps. It will thus be a great tool for scholars, students, and museums professionals, who will be able to use it as a starting point for their own investigations.

At the 2012 NEASA Conference, I will take the reception of Jackson Pollock in postwar Europe as a case study. I will describe the process of transforming the analog information available on this artist into relational database, which is then used to generate dynamic maps and statistics. I hope to demonstrate how those maps and charts not only summarize and visualize information, but also how they expose new information that allow me to challenge the official story of postwar American art.

By Catherine Dossin

Monday, July 2, 2012

Word and Image in the Print Culture of Atlantic Slave Revolt

The paper I will present at the NEASA conference this fall attempts to theorize the relationship between prose narrative accounts of Atlantic slave revolt and the illustrations that often accompanied them. Approaching the Nat Turner insurrection (1831) through the lens of media studies, I examine the tensions that exist between the content of these written accounts, which tend to emphasize the contingent and exceptional nature of violent slave uprisings—and thus the impossibility of their recurrence—and the discursive thrust of their frontispiece illustrations, which often undercuts this attempted containment. The genericized woodblock images that precede these pamphlets often operate by an allegorical logic that undermines the text’s overall efforts to render the Turner revolt a singular phenomenon. Moreover, the images’ technological reproducibility—emblematized by the fact that the image accompanying Samuel Warner’s Authentic and Impartial Narrative (1831) of the Turner revolt is recycled in an account of an entirely different uprising during the Seminole War several years later (the anonymous Authentic Narrative of the Seminole War, 1836)—gives the ultimate lie to claims to insurrectionary exceptionalism.

I am still working to verify my hypotheses about the kinds of printing networks that would have permitted the woodblocks used to create these images to migrate between the different urban hubs of antebellum printing (I have determined that the images are not merely copies of each other). As I do so, it would be very helpful to know if others involved in this year’s conference are addressing similar issues through different materials and how they are approaching them. I would be interested to hear about other projects that attempt to trace the provenance of shared printed matter and then to leverage this information into an argument about the literary or ideological content of texts.

The second question I would like to pose here involves how digital archives are making different kinds of scholarship possible. As my paper will detail, this project would not have been possible without both expansive online research into the visual culture of Atlantic slave revolt (which rendered the recycling alluded to above visible to me) and more traditional archival research (which confirmed it). Likewise, digital remediation will make it infinitely easier for me to communicate my findings at our conference and in the classroom. At the same time, it would be naïve to regard such remediations as substantially different from the ones that take place between the different texts I mention. If the tools of digital literary studies have become sophisticated enough to generate new readings of old texts, how can they also help us to view our own scholarly and pedagogical practices in new lights?

I am still working to verify my hypotheses about the kinds of printing networks that would have permitted the woodblocks used to create these images to migrate between the different urban hubs of antebellum printing (I have determined that the images are not merely copies of each other). As I do so, it would be very helpful to know if others involved in this year’s conference are addressing similar issues through different materials and how they are approaching them. I would be interested to hear about other projects that attempt to trace the provenance of shared printed matter and then to leverage this information into an argument about the literary or ideological content of texts.

The second question I would like to pose here involves how digital archives are making different kinds of scholarship possible. As my paper will detail, this project would not have been possible without both expansive online research into the visual culture of Atlantic slave revolt (which rendered the recycling alluded to above visible to me) and more traditional archival research (which confirmed it). Likewise, digital remediation will make it infinitely easier for me to communicate my findings at our conference and in the classroom. At the same time, it would be naïve to regard such remediations as substantially different from the ones that take place between the different texts I mention. If the tools of digital literary studies have become sophisticated enough to generate new readings of old texts, how can they also help us to view our own scholarly and pedagogical practices in new lights?

-Alex Mazzaferro

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)